We left Martijn walking through the streets of Vegas in 2010, feeling deeply nihilist.

Right at the start there was already shadow and, I call it, a cancerous disease.’ Another employee says: ‘Anything that is happening today has deep roots. But many employees say Synthesis had a big shadow side: ‘There was a radical difference between what was showed externally and what went on inside’, says one veteran employee. Martijn often talked in podcasts about the importance of ‘confronting the shadow’. But, through interviews with many people who worked at or for Synthesis, it’s clear to me there were deep-rooted problems from the start. Synthesis has had some high-profile problems in the last year, especially its $4 million retreat site in Oregon which turned out to be unusable for psilocybin retreats. The point of this article is to think what lessons can be learned from the situation and taken away by the psychedelic ecosystem, from the perspective of harm reduction. He’ll be in a tough place now, and I wish him well.

I know and am friends with several people who worked at or for Synthesis, including Martijn, who I met in 2018. I worked for Synthesis, or at least, I gave a talk for them on the history of psychedelics which became part of their practitioner training course. I’m not writing this piece as an outsider laughing at the misfortune and suffering of others. This month, Synthesis became the first big bankruptcy of the psychedelic renaissance, and experts say it could even bring down Oregon’s struggling psilocybin programme. That was the start of a spiritual journey that culminated in him founding the Synthesis Institute, the first psychedelic retreat company and a leading player in the US’ first legal psilocybin programme. That night, the young philosopher wandered the streets of Vegas, feeling a deep sense of the meaninglessness of the universe. He was bursting with pride as his father watched from the audience.īut then his father left to go to bed, and Martijn lost everything in two hands, and was out.

In one hand, he won two million dollars and became the leading player in the tournament.

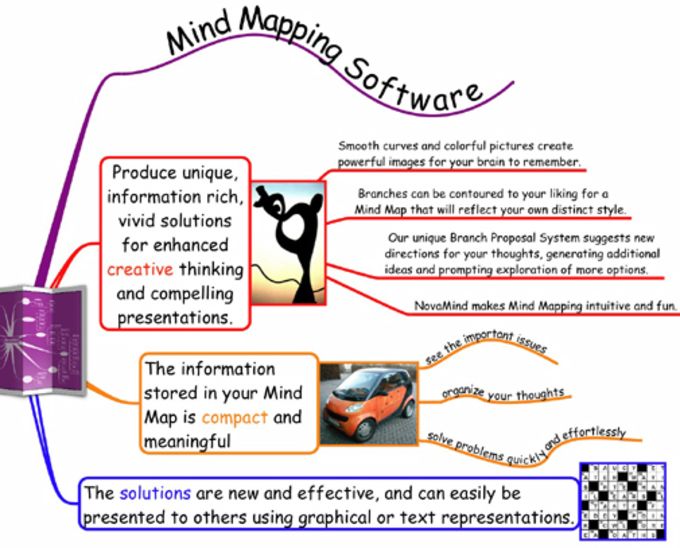

#Novamind 4 series#

In 2010, a Dutch philosophy undergraduate called Martijn Schirp almost won the World Series of Poker in Las Vegas, in which 7400 players competed for a $10 million prize. If you’re a subscriber to Philosophy for Life and missed the last email, I’ve folded that into this newsletter. Martijn Schirp at the World Series of Poker in 2010

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)